Autoweek

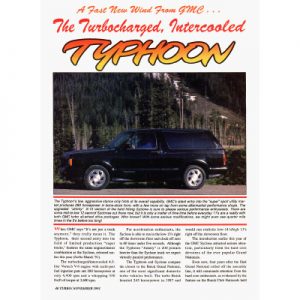

Typhoon takes Germany by storm, turning heads on the autobahn and winning new fans with its performance on the drag strip

By Mark Vaughn

After you pass the town of Weimar in what used to be called East Germany, about 90 minutes away from returning to what used to be called West Germany, the pavement finally starts to even out. You’re still in the former communist republic, but the potholes finally stop walloping suspension components to pieces, the expansion joints start to contract a little and the spectre of the decreasing-radius tum starts to fade. Almost three years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, this is about how far capitalist asphalt has reached.

It is here that the Porsche 928 laden with aftermarket wings, fairings and flaps appears in our rearview mirror. It is coming up fast-probably close to its 171 mph top speed-with the headlights on in typical Autobahn powermeister fashion. Our GMC Typhoon-albeit after a respectable performance in the East German weekend drags-is no match for this grand tourer and stays in the right-hand lane, the hatches battened down ready to be blown by.

But nothing happens. Instead the 928 slams on the brakes and hauls down from 171 mph so fast we think there must be something wrong. There isn’t. The 928 matches our Typhoon’s 100 mph, then coasts along next to us while the two German occupants leer and ogle our American vehicle, backing up traffic. GMC just might have a new market for its drag racing sport/ute.

“It’s gotten quite a bit of favorable press over here,” said Fritz Beienneister, executive director of GM International Export Sales-Europe, after we’d turned in the keys. “But there are only a few of them in Europe right now for testing.”

Apparently the guys in the 928 had read some of that favorable press. A lot of Germans had read it, as we discovered after a weekend’s worth of brisk acceleration between Frankfurt and Berlin. A Toyota Land Cruiser full of German Typhoon lovers had caused many a saluting finger as they fought for viewing position on the western side of the German autobahn. Young Deutschers in a VW Golf tried to follow along for kilometers. And when we drove it up to Alteno and entered it in a drag race, the competitors against which it ran had definitely heard about it.

“This car can do 13s, can’t it?” queried one of them.

“It’s got all-wheel-drive, right,” said another. “That’s illegal.”

We began shoveling lies the way drag racers have shoveled them for years. “Hey man, it’s just a truck,” we said in broken German. “You guys’ll blow my doors off.”

That last bit translated well. And why shouldn’t it? There are no less than three monthly magazines in Deutschland dedicated to the celebration of American hot rods and dragsters.

Germans have been drag racing in earnest since the late ’60s, when transplanted GIs lonely for their hometown strips first turned a quarter-mile on an Army airfield. The locals, lured by all the noise, tire smoke and horsepower, soon tried their hands at the sport with homemade versions of Opels, Bimmers and the requisite Detroit Iron. And now it has grown into one of the most popular forms of motorsport in motorsport- happy Germany.

So it seemed only natural that when General Motors offered a Typhoon to the European press, the Europeans would love it. Maybe a little too much. They tried to light up the tires ( which you can’t do very easily with 4wd), took it off road (which you’re not supposed to do at all, despite 4wd), turned comers too soon, chunked the tires and finally blew the transmission to pieces (this latter task reportedly accomplished by the GM Netherlands press relations office itself).

It was almost as if these jaded auto writers had discovered for the first time the visceral thrill of being stuffed back into the seat as the turbo whines and all four tires grab asphalt at a rate higher than almost anything this big and boxy should be able to attain. And they were writing their praises in their myriad motoring publications. So that by the time we got hold of the vehicle (Chevy-badged, because GM doesn’t use the GMC Truck brand in Europe), with a freshly air-shipped transmission intact, it was like taking Madonna to the prom.

Except that we took the Typhoon to the “Fourth Grand National, Internationaler Dragster-Cup Lauf & Big Power Meeting in Alteno,” what you and I might call the weekend drags. The event was one of a Seties of drag races sanctioned by the Hanau Auto Racing Association.

“Myself, two officers and two NCOs in Hanau (Germany) founded the Hanau Auto Racing Association in 1969,” said Jerry Lackey, dean of drag racers in Germany. “The major purpose of the club was to give the American military man some off-duty action and a little taste of home away from home.” At its peak in the mid-1980s HARA ran 10 to 15 weekend drag races a year at U.S. Army airfields.

Now, drag racing is a naturalized German citizen. While HARA started out with a majority of its participants coming from the U.S. military, time, world politics and the international appeal of quick ETs has reversed the membership. Today, almost all the racers are German, with some from Sweden, Switzerland and Denmark as well as a handful of retired or soon-to-be-retired U.S. Army NCO’s.

The Big Power Meeting was held at what was, only months beforehand, a Soviet airfield. Somewhere nearby, a few buildings make up the town of Alteno, but you can’t see them from where the race was run. This was strictly farmland and forest with two mile-long landing strips in the middle. The Soviets have cleared out, but as you drive in you can still see the jetways leading off into the trees with their cement blast-deflectors in place, still awaiting the big scramble that never came.

The few buildings at the airstrip house refugees that Germany has taken in from all over the world. As we drive in, the refugees peer through fences at the long line of bizarre and seemingly purposeless machines being trailered and driven up to the scrutineering bays for tech inspection. Though they can easily walk over and have a look, none of the refugees wandered over to poke-around under any hoods.

Had they come, they would have gotten a closer look at everything from stock-looking VW Beetles to full-blown . alcohol dragsters. Many racers showed up with turnkey machines purchased in the U.S. and shipped over in crates.

“Some of these guys have more money than sense,” said Clyde Wellman, who was in the tech inspection line in front of us. Wellman came to Germany in 1983 as a U.S. Army Sergeant First Class and now works as a civilian for an Army subcontractor in Berlin. His spare time and money go into a nitrous-fed 5.0-liter Mustang GT with rear tires as big as bass drums. Since he built the car with the help of many German friends, Wellman speaks two languages: English, and English with a German accent. This amuses the Germans no end.

“All these years and this is as good as he gets,” jokes one of his fellow racers.

The friendship between Wellman and the German friends who share his paddock space is typical of the camaraderie on a race weekend. When Wellman discovers we’ve shown up without the requisite helmet or fire extinguisher, he quickly arranges to have them for us the following morning, for Saturday’s first round of qualifying.

The Typhoon is entered in a class called “Public Race,” where the only requirement (in addition to the helmet, fire extinguisher and a long-sleeved shirt) is that the car be legally registered to drive on German roads. We’d promised to get the first three requirements and no one said a word about the Michigan license plate affixed to the back bumper.

Saturday morning, we line up next to a red-and-white Mustang Mach 1 with a jacked-up rear end, very large tires, a decidedly un-stock rumble under the hood and Berlin registration plates. There is a crowd of about 1000 or so race fans lined up in bleachers and along the fence.

In a few practice starts we’d noticed an space is typical of the interesting challenge about drag racing the camaraderie on a race Typhoon: the 4.3-liter turbocharged and intercooled V6 can overpower the brakes, as man discovers we’ve is most definitely not the case with the majority of street-legal vehicles.

This made brake-torquing a rather tricky proposition. Up to 2000 rpm the boost gauge stayed at zero and the brakes held the truck in place. At over 2000 rpm, it became increasingly difficult to keep it from jumping ahead. Once the Christmas tree blinked into the “staged” mode, any forward movement would cause a red light, disqualifying the run.

So starting would mean very, very delicately brake-torquing until about the time the last yellow came on, then sliding the left foot off the brake, keeping the right foot on the gas, steering as close to straight as possible and letting the automatic transmission do the rest.

We eased up to the line. Prestaged. Staged. The Mach I did the same. Instantly yellow lights blip down the tree. Look at the tach or the Christmas tree? Don’t know. Look at the tree and estimate the tach. O.K., look at the tach quickly just once. Just under 2000. Now the tree. Lights racing down. Last one. Do what? Argh, go, GO!

The Mustang is making an awful lot of noise. Engine noise, tire screech. Peripheral vision sees blue smoke from its tires. The noise, it sounds like … horsepower.

The Typhoon is relatively quiet, almost silent but moving fast. Yes, faster than the Mach 1. All four wheels grip while the Mach I spins its rear rubber. We get away and keep going. The crowd cheers, always rooting for the underdog, the silent, unpretentious Typhoon pulling away from the brawny Mustang. The cheering fades as the quarter-mile looms, way, way down the track.

The flag at the finish line passes and no Mustang. We win! This drag racing stuff can be a lot of fun.

A look at the time slip later shows a 14.217 at 88 mph, about the same as the U.S. magazines were getting back home without having to wait for the green light before hitting the gas pedal.

But in drag racing you’re only as good as your last quarter-mile. In the next heat we line up against another Mach 1 that gets about a car length on us at the start and holds it evenly for the rest of the way. We lose by 0.2 of a second.

The next two runs are against VW Beetles that arrived on trailers. One turns a 14.075 and the other is in the low 12s. We’re humbled, but our first run is good enough to qualify us 11th and get us into the Sweet 16 who get to race in the Sunday show.

That night, as the sun dips low over the Luckenwalde Valley, racing continues. Six classes of motorcycles and four of cars keep the audience interested. Just before darkness descends, we watch from the roof of a bus parked near the starting line as three huge military trucks roll through the paddock gates. The writing in the corner of the windshields is strange, the Rs are backwards. These are leftover Russian troops arriving with klieg lights rented by HARA for the Saturday night drags.

How about this New World Order, eh?

On Sunday, of course, we’re blown out of the water in our first race, thankfully not by another of those infernal trailered Beetles but by a Blue Corvette Stingray with more plumbing under the hood than a Roto Rooter truck. With several inches of fiberglass fender flares to accommodate larger tires, the Corvette whips out a 13.311 to our relatively lame 14.575. We console ourselves with the knowledge that we’re the fastest—and probably only—totally stock vehicle in the show … and we’re suffering jet lag … and we never got a chance to practice shifting … and … and … and ask any drag racer.

Our early loss gives us time to chat up a few locals. Steven Campioni is a German who has been drag racing five years, starting with a BMW M5 he’d tweaked to put out 450 hp. (“Then I have seen the Beetle and I have changed.”) He was looking to buy a Typhoon during a recent visit to the States, but couldn’t find a dealer who’d let him test drive one. We let him.

“The steering is better for driving,” he says cruising down the access road formed by the left runway. “You’ve got the feel for the road.”

He tries a kickdown at about 20 mph. We lunge forward. “Good, good,” he says. The turbo impresses him, he says, but the car is far from perfect for the price.

“The interior is nice but I don’t like the buttons,” he continues. “Too much plastic on the inside and outside. For 70,000 deutschemarks ($42,500) it’s not enough.”

Campioni could buy one in the States, ship it to Germany and convert it to German specifications for about $33,000 but says the time and effort to do so wouldn’t be worth it. Plus he’s heard other stories (not ours) complaining about transmission troubles. We mention that the towing capacity is 500 pounds and he lets out a long “Oooooooh.”

Campioni says he will likely order a fully loaded Jeep Cherokee, which is “more practical” if not as fast as the Typhoon, and has, in his eyes, less plastic.

We do not succeed as Typhoon sales reps.

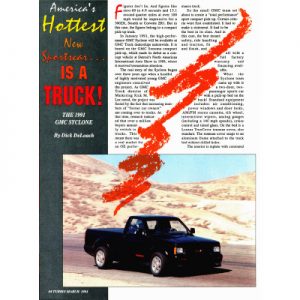

A GMC Syclone is parked in the paddock and we amble over to inspect it. It belongs to a Swiss racer. We ask if he’s planning to enter it in the races. No, he says, he’s using it as a tow truck for his race car, a turnkey dragster wearing the body of a ’57 Thunderbird and boasting all the racer tricks. We just don’t have the heart to tell him about the rated towing capacity, figuring he’ll probably discover that about halfway home to Switzerland.

Many of the more serious-looking entries are bought lock, stock and four-barrels in the U.S. and shipped over to Europe by those with enough cash to get serious about being quick. Others are home-built, like the air-cooled Volvo four-cylinder or the various guises of Opel Manta. Most of the U.S. cars still have their original paint jobs and sponsor logos, giving international exposure to body shops in Michigan and parts stores in Southern California.

Near the starting line at the afternoon semifinal rounds we run into Bemd Schuman and Detlef Zechel, the drivers of the two Mustang Mach 1s. They are both in their mid-30s and in America might be called . yuppies, except that they build and drive their own race cars. Together we watch two of the hated Bee- : ties go head to head.

“They’re street legal,” says Schuman. ‘Yeah, they go home and put the stock engines in them and then they’re street legal.”

Having each been bested by Beetles, we gain a sense of fraternity hating the cursed Volkswagens. Schuman, whom we had rousted in the first heat Saturday, can’t believe our Typhoon was eliminated so early and easily today.

“In the first round,” he questions. “But your car can go 13 seconds, can’t it?”

We try to explain that that’s in more or less ideal conditions, where the clock starts as soon as the truck moves, not as soon as the green light goes on. Of course it wasn’t any fault of the driver, we say.

“Why do you guys like drag racing?” we inquire.

“Why?” Zechei asks, and turns to Schuman, “Why?”

“The atmosphere of the race weekend,” Schuman explains, counting off each reason on a subsequent finger, “to get a chance to drive these cars as they are meant to be driven, and because it’s fun.”

“And why Mustangs?”

“Because everyone else has Chevys,” Zechel says, “We want to represent the other side.” Then he adds, “And, because it’s American.”

We ask if this last qualifier is good.

“Yes,” he says.

Driving back to Frankfurt that night over East German autobahn as badly pockmarked as the legendarily rough interstate (1-94) between the airport and downtown Detroit, we consider the marketing plight GM faces.

Do Europeans, who have grown up with Mercedes, BMWs, Ferraris and Porsches really have an interest in a vehicle whose sole purpose is to dust the competition at stoplights? Can they justify the lousy gas mileage (we got 13 mpg on our weekend), live-axle rear end with a mind of its own, and boxy, plasticky looks? Is Europe ready for a 13-second (more or less) quarter mile from a truck?

As we’re contemplating these heady questions, the 928 slams on the brakes and its occupants stare in admiration at our Typhoon. We figure that, yes, Europe probably is ready.