Autoweek

By Mark Vaughn

Ram tough. Ford tough. Like a rock. Clearly, pickup trucks are not marketed to ballerinas. The image truck marketeers want to convey is a product with all the sturdy reliability of a shovel.

Which is how the pickup truck started—as a simple farm implement. It filled a role as rudimentary as the dirt plow. It was made to haul cows, hay, diesel generators and sacks of feed. And, oh yeah, there was this little space up front where the cowboys sat.

No one expected much more of them. They required an engine up front (so the bed could go in – hack) rear wheel drive (for traction and towing) and the bed had to be as big as would fit on the frame rails to carry as many large, odd-shaped items as possible. The passenger compartment— preferably one that could be cleaned out with a garden hose—was almost an afterthought. There was one size— big—and there were few amenities.

Pickups ambled along like that for decades. It wasn’t until the fuel crunches of the 1970s that they began to play new roles. That was when Japanese truckmakers introduced incredibly small (by comparison) versions of the traditional American hoghauler. These trucks—like the Chevy Luv, the Ford Courier and the Nissan Lil’ Hustler —all came into the U.S. market as vehicles for first-time buyers.

“That created a youth appeal,” said Keith Helfrich, Dodge Truck marketing plans manager. “It became an entry-level vehicle.”

Instead of beat-up, second-hand passenger cars, first-time buyers were handed a whole ‘nother category of vehicle, one with immense versatility as well as low cost.

Then, six years ago, Dodge introduced the Dakota, which created the midsize truck niche. Toyota will follow Dodge’s lead, and there are rumors of a midsize Ford pickup in the planning stages.

So today we’ve got three basic pickups” to choose from: small, medium and large. And, as pickup sizes change, so do their uses. About the time the minitruck market grew, another facet of the pickup market—the pickup aftermarket—was born.

“Things like the slide-in campers came into being in the ’60s and ’70s, and suddenly this farm vehicle became a recreational vehicle,” Helfrich said. “Suddenly you could do things with them that maybe you couldn’t do with cars. That had a lot of appeal.”

Add the extended cab, and the pickup truck finally got off the farm and into suburbia. Sales took off. According to Frank Stavale, manager of strategic marketing planning for GMC Trucks, what began as a 10- to 15-percent share is now a third of the total light vehicle market, and growing.

“We’re looking at the market leveling out at maybe 50 percent cars, 50 percent trucks,” Stavale said. “The application of trucks has grown from work to filling a number of roles in the family and lifestyle stages of the American public.”

As those roles grow, truckmakers are scurrying to find new ways to fill them. And with each new role they discover a new way to make the pickup truck more appealing to more buyers. Some marketing analysts would call these niches.

“There are a lot of people who have a different image of what pickup trucks do than we traditionally think of,” said Leo Williams, Ford Division marketing plans manager for the F-Series and Bronco. “These are people who are buying pickups because they have a functional use for them but at the same time they see there is an opportunity to have some fun.”

For Ford that fun means Flaresides and Nites, standard F- 150s that make their own styling statements. Other makers have “custom” trucks, each exploring a new niche of the market, some quite small.

GMC’s Syclone supertruck, for instance, can dust Corvettes off the line but can’t carry more than 500 pounds in the bed or tow anything. That’s a niche.

The Chevrolet El Camino and Ford Ranchero were in niches. Because they were derived from passenger cars and could only carry 500 pounds, they lost a lot of the functionality buyers seek in a pickup, which contributed to their demise. Turns out it’s function that buyers want first, everything else comes after that.

“The problem with the Al Ranchero was it was not a car and it was not a truck,” said Williams. “If you are going to do something like that then you have to give people the ability to do all of the stork-type things they have to do and yet still be comfortable in the cab’s environment.”

In other words, if you want to make it more carlike, that’s fine, but it still has to be useful. Enter the extended cab.

“It gives them a capability that is unique, the ability to do things functionally that they can’t do with a car,” said Williams. “And at the same time gives them the ability to carry a family comfortably.”

And it makes it easier to justify a pickup over a sedan as a “first car.” That and a more car-like interior (once thought of as a near-insult by old-timers) are pulling pickups into the mainstream.

“I remember in the 70s working on a proposal to put automatic door locks on trucks,” said Dodge’s Helfrich. “It was like, ‘Who the hell would ever want to spend that kind of money on power door locks?'”

Today there are plenty of people who would. Amenities once thought of as “carlike” are now standard fare on pickups. In fact, finding a bare-bones model can be difficult on some dealer lots.

“The distinction between cars and trucks will continue to get smaller and smaller,” said Williams.

But at the expense of functionality!

“Absolutely not,” Williams said.

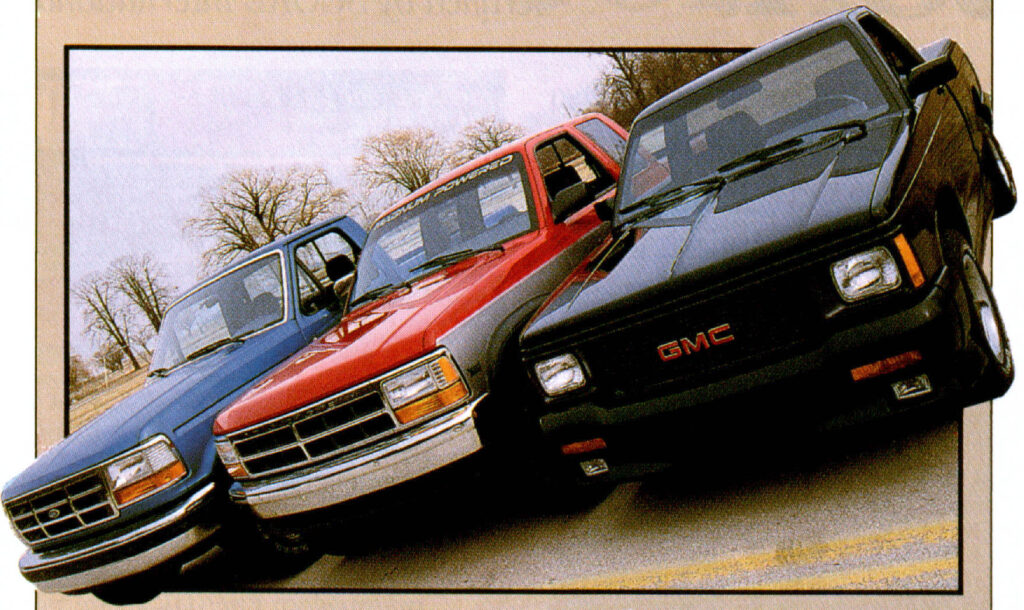

For our 1992 SpringFile, we took three of the new breed of pickups and ran them through our AutoFile barrage of tests. We chose a large, “customized” truck, the Ford F-ISO Flareside; a medium truck, the Dodge Dakota with the new Magnum V8 and Club Cab; and a small, sporty truck, the GMC Sonoma GT. Beginning on page 21 you’ll find what we, and owners, think of the current state of the pickup in America.