Autoweek

With the 454SS joining Syclone as spent blanks in the marketplace, is the Lightning on-target, or another sport truck shot in the dark?

By John M. Clor

It doesn’t seem that long ago when enthusiasts viewed a truck as … well, a truck. It was considered little more than a work vehicle that some people had the audacity to drive on the street. Or a farm implement pressed into personal transportation service for those poor, unenlightened souls who don’t understand the satisfaction attained from a sporty automobile.

There were truck lovers and there were car enthusiasts, and very few of either belonged to both categories.

Today we have a choice of good-looking, high-powered pickups that can haul passengers and a good-sized load as well as they can haul the mail for the performance-oriented driver. They’re known as “sport trucks,” designed to convey the driving character of sporty cars while retaining the all-around utility of a pickup truck.

On the surface, it would seem an easy task to interest performance car people in pickups. But a deeper look tells us that it’s not as simple as we’d like to believe.

By now many of us have seen all the head-to-head comparisons in the monthly car and truck buff books between two of this year’s biggest and baddest sport trucks: the Chevrolet 454SS and the Ford Special Vehicle Team F-150 Lightning. Yes. they’re both full-size pickups with full-boogie V8s that generate similar times on the dragstrip. We’ve driven both, crunched the same numbers, and feel that-as enthusiasts-the question of which truck is better is a moot point.

Why? Because while the ’93 SVT F-150 Lightning is the new kid on the block, next year it’ll be the only bully around: The 454SS will not be available as a 1994 model. GM decided it wasn’t worth the expense to certify it for CAFE and emissions, and pulled the plug. Certainly, sales numbers were a big pan of that decision: Though the 454SS was welcomed to market in 1990 with some 13,000 sales, that figure dropped to about 1000 in ’91 and ’92, and only 759 so far in ’93. So much for instigating a new Ford-Chevy rivalry.

Consequently, the question becomes: Why did the 454SS fail, and how does that impact on the fate of the SVT Lightning? Consider, too, the birth and quick death of the GMC Syclone, and it becomes an even bigger question: When three blockbuster sport trucks are launched within 48 months of each other and two-thirds of them die in that same period, what does it mean to this market?

If some of you feel compelled to add “Who cares?” then you haven’t been paying attention. As we noted in our cover story on the ’94 Dodge Ram pickup (AW. May 17), by now it should be obvious to even the stringback-gloves set that trucks are happening. Fueled by the proliferation of extended-cab pickups. sport/utilities and minivans, light trucks account for nearly a third of all vehicles sold in this country.

Which means many car enthusiasts are already driving them to tow a race car, haul an old classic around, in their work or even as an everyday driver. But who says we can’t have a utilitarian vehicle that offers an enjoyable driving experience to boot?

That’s precisely where the idea of a properly executed factory sport truck has captured our interest. But it’s increasingly apparent from the failures of the Syclone and now the 454SS that while automakers seem willing to try, they’re still groping for a concept that will click with enthusiasts.

First, realize that even as the Lightning is establishing itself and the 454SS is in its final year, these are vehicles coveted mostly by those already in the truck market. If the sport truck niche is to grow like the overall truck segment has, the products must induce crossover sales from the car market. If sales success is the yardstick here, there are many more lessons to be learned about what makes a car buyer consider a truck before product planners can devise new models that are embraced by both truck fans and car enthusiasts.

To accomplish this, let’s first make it clear that in our definition of a sport truck, having power and handling is a gimmie. Without both, you’re talking an also-ran. Then let’s establish three parameters we think are necessary to address the needs of an enthusiast truck buyer. Using them as a guide, we can not only center our comparisons on how each past and present product stacks up but also what was or is wrong or right about them, as well as what will be needed to ensure success in the future:

1.) It’s got to be a truck first: Few enthusiasts will ever see a pickup as a sports car, no matter how hot, so give them what they’d want a truck for in the first place- a truck, with full hauling and towing ability.

2 .) It’s got to be the right model: If buyers are to enjoy car-like practicality, a sport truck should be built off the most car-like, most useful model available.

And 3.) It’s got to be priced right: Enthusiasts have long been able to justify the cost of a sporty car, but the idea of doing so for a truck is new to them, even if performance numbers are similar.

That said, the case of the 454SS becomes clear. Its strength is easily its straight-line acceleration: 255 hp worth of tire-churning power, good for that impressive 7.5-second 0-60 mph time (AW, March 18, ’91 ). But staffers aren’t as impressed with its handling. While the rear end feels light, allowing you to burn rubber just by mashing the throttle and enticing you to sprint around in traffic, it feels equally as light when entering a sweeping turn or diving into an onramp- read “light” as in devoid of grip. Ride is somewhat jouncy thanks to stiffer springs and Bilstein gas shocks putting 15- inch BFGoodrich rubber to the road.

Real enthusiasts don’t merely drive stoplight to stoplight, and a one-trick pony can become tiring . Performance also has to carry around bends in the road, so the 454SS’ lack of handling sophistication cripples it even before we apply our formula.

Doing so reveals that while the 454SS can perform most truck duties with a sizable payload rating, it has a diminished 6000-pound towing capacity, less than half of what the top-rated C/K can tow. Though the standard C/K has the roomiest cab in its class, the 454SS is not available as the more practical Extended Cab; and neither the option of a bench seat nor a hard tonneau with cargo nets for storage in the pickup bed is available, posing problems for the daily driver. And while its $21,250 base price is relatively affordable, the risk of pricing it beyond the means of the blue -collar truck buyer increases as you go beyond the magic $20K mark. And there is no “stripper” option with the same mechanicals but fewer amenities.

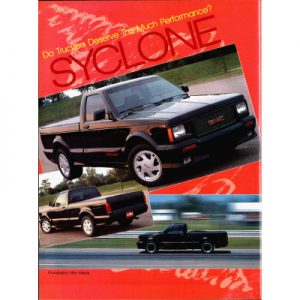

If those shortcomings doomed Chevy’s big brute, look at an even more potent performer GM brought to market about a year after the 454SS: The GMC Syclone.

It wasn’t until real performance found its way into today’s trucks that most “car types” began to pay much attention. And you can bet that when the compact turbo V6 Syclone was introduced (AW, Oct. 1, ‘ 90) with a claimed 0-60 in 4.6 seconds and the quarter-mile in 13.4, even sports car buffs took notice. But the Syclone blew out after the 1992 model year, despite its advantage of being a smaller, lower, lighter truck with vastly better handling, 4wd and superior all-around speed. Why? With no towing ability and a payload capacity of a mere 500 pounds, Syclone abandoned its truck roots.

Many believe GMC doomed the Syclone by restricting it to standard-cab only; the extended cab version would have offered far better seating capacity and needed storage, giving it greater versatility (See story, page 25). As a standard-cab two-seater, there was no room for a third person or any carry-on baggage. It ignored the need to still be a truck yet serve as a car. Now its sister sport/ute spinoff- the Typhoon-soldiers on alone, thanks in no small part to its functional edge despite the lack of a four-door model.

To cap it off, for the Syclone’s sticker of $25,500 you could buy an established sports car, or any other number of traditional sporty cars. Had it been de-contented and priced cheaper, it could have made money with volume and still raised image.

Yet even before the effects of the marketplace could fully influence many decisions, Ford was readying a competitor: Enter the 1993 F- 150 Lightning. The call went to Ford’s Special Vehicle Team; The idea was to one-up the 454SS and skip the Syclone’s more technically exotic ambitions.

Acceleration first: Tests generally peg the Lightning a tick slower 0-60 mph (7.6 seconds) than the 454SS and a tick faster (15.6) in the quarter-mile, and driving SVT’s F-150 bears out the impression that the Chevy’s 65 lb ft torque advantage is best felt at launch. Lower reciprocating mass and better breathing in Ford’s high-output 351-cid Windsor V8 help negate the 454SS’ extra 15 hp at higher rev ranges.

But what sets the Ford apart? Seven and a half seconds to 60 puts both trucks better than such acclaimed sporting machines as the Acura Vigor (9.0). Lexus ES300 and Pontiac Bonneville SSEi (8.8), Audi 100 (8.6). Subaru SVX (8.5), and Honda Prelude Si (7.7). just to name a few. And it puts them in the ballpark with no less than the Lexus SC400 (7.5) and BMW 325i (7.4) But what makes those cars desirable to the enthusiast is not only acceleration, but that they can also handle a corner. SVT figured that while both the 454SS and Lightning could be fast, just one- their Lightning- would seriously address the handling pan of the equation.

SVT worked its best magic in the suspension, to put the Lightnings more serious 17- inch Firestones to the test. Lightning’s cornering prowess tests your prejudices about pickup truck handling: you can find yourself reaching a mental limit (this is a truck!) far before you reach its limits (A W. Oct. 26, ’92). Ride is firm but quite supple over all but washboard surfaces, and steering feel is among the best we’ve sampled in a Ford product, let alone a truck.

Being so new to the market now begs the question: Will stunning handling be enough to ensure Lightning’s success, or will it be left to spin its wheels as just another flash in the sport truck pan?

Our sport truck formula notes a payload slightly below that of the 454SS, but also that Lightning has better towing ability, up to 8400 pounds with the right options. Its strength here is aimed at what an enthusiast might want a Lightning for: Towing a trailer. Driving this point home for us was a Lightning owner we spotted recently at Detroit Dragway, who raced his monochrome-red Lightning, and then his monochrome-red ’66 Fairlane, before pulling it onto his matching red trailer for the trip home. How many enthusiasts double their track time racing a competitive tow vehicle?

Like the 454SS, the Lightning is not available as a SuperCab. Worse, the older design of the F-150 cab isn’t as roomy as the C/K-based Chevy, and again, there are no bench seat or hard tonneau/bed storage options. And while the base Lightning isn’t as well-equipped as the 454SS in some areas, its $19,523 price tag is in the ballpark-though you can’t go down from there with a stripper version, either.

So where does that leave us for 1994 and beyond? We know that styling and performance are important. and now see that handling and versatility are also musts. But to find out where we are going, it sometimes helps to find out where we’ve been. The sport truck idea isn’t a new one. Mopar fans will remember Dodge’s Li’I Red Express of the late-’70s, or the black-and-gold Warlock. But most specialty full-size pickups in the past decade merely consisted or appearance enhancements.

That’s not to say the Big Three hasn’t tried. GM carried a list of “sporty” options ever since the full-size C/K line bowed in ’88, including the Sportside flared rear-fender treatment. Ford came out with its F-150 Nite package (AW, Jan. 28, ’91), and its own FlareSide bed.

There were more choices in downsized trucks, with Dodge again leading the way: Dakota could be had in Shelby guise (AW, Aug 28, ‘ 89) earning its stripes with a 175-hp 5.2-liter V8, good for a 8.5-second 0-60 time, as well as a unique Sport Convertible (AW, Feb. 26, ’90). In compacts, Chevy reincarnated the Cameo name for a gussied-up S-10 with a 4.3-liter V6 and Getrag five-speed, and also offered a Baja 4×4. Ford’s response was half-hearted, dressing up the Ranger and calling it a GT in 1988-89.

Looking back, GM deserves credit for taking that bold, initial step to redefine the segment with the 454SS. And GMC gets kudos for the Syclone, which has forever left its mark on the genre by packing carlike excitement into a pickup; it remains a truck performance landmark to this day.

By our own formula, the Lightning is the most balanced shot taken to date. But now we not only see how Ford might dodge the bullet with its planned 1994 and ’95 Lightnings to improve their chances of survival, but have triggered a challenge for PN96: Will SVT performance and a new sense of utility be pan of the redesign due for F-150 in 1996, or will it miss the target?

We’ve heard rumors of an independent A-arm type front suspension replacing the old Twin-I-Beam unit, and of a new modular V6 and V10, as well as a 5.4-liter highoutput version that we’re certain SVT would love to add to Lightning lore when the roomier, more stylish ’96 F-150 bows.

Surely it’s time for someone to risk a new entry: GM might be wounded but should not be counted out, and Dodge could ambush anybody with a sport version of its new Ram. And if a taste of leadership lingers in the heart of Ford, then it’s possible the sport truck market might play right into enthusiast hands.